Ben Horowitz's diving catch

How the a16z co-founder pivoted long before the concept had been named.

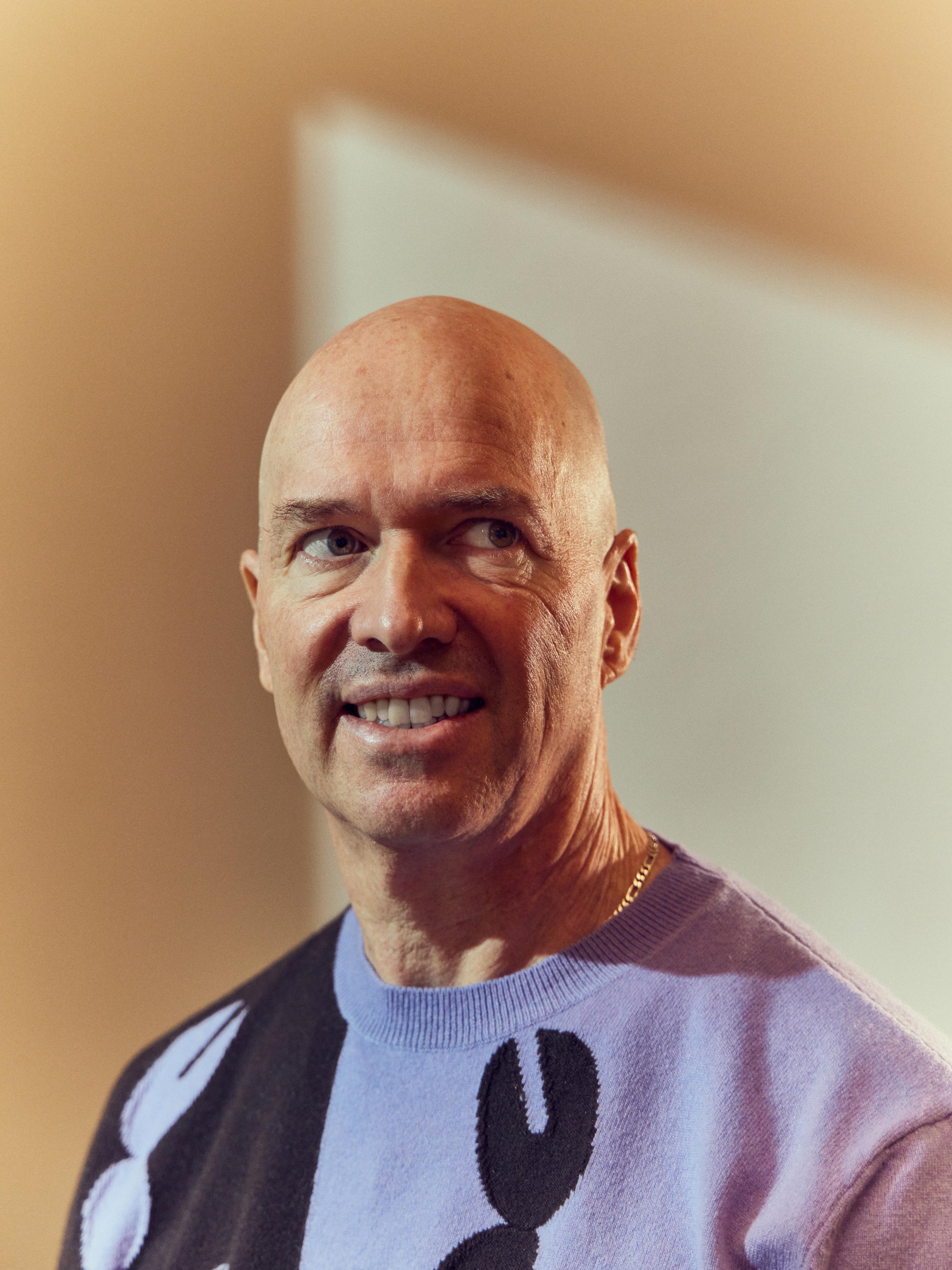

Written by Meghna Rao

Photography by Derek Yarra

There are some who might say that history hinders the future, that the arc of innovation must bend freely in the direction it chooses to without paying homage to what has come before it. And there are others who would say that the past can be a corrective lens that might strengthen your vision, give you answers, and help you understand our current times better.

The latter is where Ben Horowitz, the co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz sits. By managed AUM, Andreessen Horowitz is the largest VC fund in the world. But a16z is not just behind major deals; they are also one of the primary engines behind Silicon Valley, the archetypes that high-growth founders strive towards — persistence, resilience, inventiveness.

Which is why I am talking to 56-year-old Horowitz in 2023 about a quick succession of months that happened nearly 21 years prior, a time in his life that influences how he invests, what he invests in, and who he invests in. “I wouldn’t want to relive it,” he laughs. “It was a difficult time for me and everyone involved. But it’s a character-building experience and nothing else can match it in life.”

Horowitz smiles big, and this feels like a stark contrast to the dark, paranoid experiences he’s described while building his startup. And yet, he has no trouble dipping back into these times. Suddenly, we’re in 2001. The Nokia 8250 had just been introduced with the world’s first monochromatic display. The year’s box office hits were Harry Potter, Shrek, Monsters Inc., and The Lord of the Rings. The Fed would cut interest rates 11 times. 9/11 and the Enron Scandal happened back-to-back.

And the dotcom crash was spreading like a wildfire. Internet millionaires had been created and destroyed overnight. 2000 had culminated with internet stocks declining in value by 75%. There were whispers in the industry that the internet would not fulfill its full potential, that the whole thing had been a fool’s bet.

It was in this environment that Horowitz, CEO of Loudcloud, would successfully pivot his business, long before the concept of pivoting had a name. And in doing so, Horowitz would come to establish one of the beliefs that Silicon Valley is structured on — that businesses can, with the right tools, pull themselves out of near-death situations and emerge with wins.

“Nobody called it a pivot in those days,” he says. “They were just like — oh, they’re going bankrupt and this is how they’re going to stave it off. And I classified it not as a pivot but as desperation. Last dive. Hail Mary. Whatever you want to call it. We’d been through so many problems before. But in retrospect, it was definitely a pivot.”

~

Loudcloud, founded in 1999 by Horowitz, Marc Andreessen, In Sik Rhee, and Dr. Timothy Howes, had a pitch now familiar in Silicon Valley — that startups should focus on their missions and outsource the extra stuff — like Stripe’s seven lines of code to set up payments or Squarespace to set up a site. Or Loudcloud for IT infrastructure.

As Wired described it in August of 2000, Loudcloud created “custom-designed, infinitely scalable sites that blasted off a virtual assembly line,” and would “automate the process of building and maintaining Internet sites in order to provide Web-hosting services on an unprecedented (and unprecedentedly lucrative) scale.” Put simply, Loudcloud automated the process of building and maintaining internet sites, so web-hosting services could exist on a large scale.

On paper, Loudcloud had all the right materials for startup success. The internet was a new gold rush and everyone was looking to build as quickly as possible. Horowitz surmises that Loudcloud might have been the fastest-growing business of all time. In just six months, the company hired 200 employees. In nine, it booked $27M in contracts.

The team was star-studded. Andreessen had long since established his position as a Silicon Valley wunderkind, launching and selling Mosaic and Netscape, the latter of which Horowitz had joined as a project manager in 1995. Horowitz, Andreessen, and Rhee had worked together at AOL, which had acquired Netscape. Howes had been the co-inventor of the Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), the internet directory standard that’s still in use to this day.

And the idea came from the founders’ own experiences. Every time Rhee tried to connect an AOL partner on the AOL ecommerce platform, the site would crash. It couldn’t handle the traffic load. This made it difficult to deploy the software to scale.

Hence, Loudcloud. Product, team, market — all a fit.

Everything we learn about decisions is: right answer, wrong answer. My situation was one where both answers were wrong. I just picked the better battle.

But Loudcloud existed in a shaky environment. The company’s success was contingent on a precarious bet: that the demand for Loudcloud’s services would balance out the hefty infrastructural costs that they came with. The dotcom boom had made betting on this demand seem like a good idea — but then the bust had rendered the thesis weak. The company was losing contracts and other similar businesses were starting to show cracks.

“LoudCloud was a catastrophe the whole way, so my decision-making leadership muscles were extra strong,” Horowitz remembers. The end of the road seemed near. “There was no way out. I could have laid off every single employee and we still would have gone bankrupt. That was the kind of capital we needed. I wasn’t sleeping. It was the first time I understood what cold sweats were — I was sweating up a storm in the middle of the night and, somehow, I was still cold.”

“I said to myself, you’re going to lay off all your employees. You’re going to fail all of the customers who trusted you. They’re going to get fired because they used your cloud computing infrastructure, and now you’re going to bankrupt this business. Everyone who invested in you is going to lose their money and your reputation will be ruined.”

“And then, what about everyone who works at the company? It’s their time. It’s your job as leader to make it worthwhile. How could you quit with that? How can you walk away? My mother bought stock in this company. How could I imagine that I could quit?”

This was Berkeley-raised Horowitz’s thinking pattern. For days, he walked around repeating the possibility that everything he had built would come crashing down. He had a wife and two kids at home. Pedigree was still rife in the job market, even in Silicon Valley; a younger Horowitz had been told by a recruiter that his chances at getting the Netscape job were low because he didn’t have a Stanford or Harvard MBA. Rational or not, Horowitz saw his failure as something that would push him off this high-growth train once and for all, and push him back to where he had come from: a child of parents who did not have access to the future who had gotten where he was out of sheer determination.

“One of the reasons I relate with hip hop is because I always feel like I made something from nothing,” he says. “I didn’t go to business school. I didn’t have any money. No one in my family was in business. So I never felt like I was protecting something I had. I had nothing and I was trying to build.”

“You have to ask yourself in that situation: who do you want to be when you grow up? Then, you have to be that now. Keep death in mind at all times. Do it the right way now because it may be the last time.”

One day, Horowitz decided to set his worries aside and to take an objective look at his business. He decided to ask himself a different type of question.

What would he do if Loudcloud went bankrupt? It was like a lightbulb had been switched on. If Loudcloud went bankrupt, he’d pull one small strand out of what remained — Opsware. Opsware was a little unit inside the company that they’d created to automate running the cloud. It didn’t have the infrastructural requirements that Loudcloud did and landed more in the direction of what Horowitz imagined the future might look like.

I ask Horowitz if he ever doubted that this was the right decision. “Not for a second,” he tells me. “Everything we learn about decisions is right answer, wrong answer. My situation was one where both answers were wrong. They were both bad decisions. I just decided to pick the better battle.”

~

Working on Opsware was like starting from scratch. Opsware was not a whole product yet and it certainly had no clients. In no world could Horowitz’s decision to pivot to Opsware be like flipping a gear. 440 of the 450 employees worked in the cloud business, which generated 100% of the revenue.

Each day brought new challenges. One came in the form of the bankruptcy of Loudcloud’s largest client Atriax, a foreign exchange trading site. Atriax couldn’t pay up the $25M they owed to Loudcloud. That also meant that Horowitz couldn’t raise the $50M he’d planned to through a PIPE (private investment in public equity) to build out Loudcloud. No $25M, no $50M. $75M short.

“We were going on the PIPE roadshow on that Tuesday morning. And that was when I got the call.” Horowitz put down the phone. He was sitting in a meeting room in Palo Alto with his head of HR, unable to speak. “Her lips were moving, but I couldn't hear anything she was saying and I was just stuck there,” he remembers. “And she says: Ben, do you want to have this meeting later? And I was like, yes. And then I just kind of went deaf.”

Still, Horowitz pressed on. “The thing that nobody got — every observer, everyone who wrote about it, everyone who dumped our stock so it dropped to $0.35 a share — what they didn’t get was that the trend was real,” remembers Horowitz. “The problem the software solved was real. We just weren’t in a financial position to capture it.”

“When you’re building a company, you're in this race against time where you've got to succeed before somebody else does or you run out of money and you’re kind of toast. I always had a good sense of that race.”

They decided to sell the remainder of their business to Electronic Data Systems, and Loudcloud decided to pivot and focus entirely on Opsware.

“I’ll never forget the reporter who asked me in 2001 or 2002, as everyone was leaving Silicon Valley and it was just death and destruction for businesses: why would you put yourself through this? And I remember thinking — do I have a choice?”

~

Pivoting was coined by Eric Ries in The Lean Startup (2011). Today, it’s nearly a Silicon Valley meme. Sometimes, it’s used as to describe the worst of what Silicon Valley behaviors have wrought: Facebook’s temporary newsfeed updates to prioritize video in 2015 that decimated entire media startups as they followed suit and “pivoted to video”’; the 2022 “pivot to crypto”’s quick evolution into 2023’s “pivot to AI”; Silicon Valley’s seemingly mission-less urge to pivot on a moment’s notice, irregardless of the real-world impact.

But just because it’s easy to move fast doesn’t mean one should shift their mission quickly. Horowitz’s pivot didn’t necessarily solve his problems; Opsware continued to struggle for years to come.

“A lot of people pivot when they shouldn’t,” he says. “If you have time and money, the idea that your new idea will be better than your old one isn’t right. Maybe you haven’t worked hard enough on the old idea. We didn’t have that problem. There wasn’t a pivot, I was only thinking — OK, diving catch.”

Horowitz places most of the emphasis on keeping his team confident and empowered. On the week that the Opsware idea came around, Horowitz worked with Howes to develop a plan. He created Oxide, a secret unit within the company to build the product. And he didn’t share this bet with the wider team until much later, when things became much more dire. His primary goal was to ensure that the people that worked for him trusted him and felt confident in his leadership.

“I remember I had a similar conversation about leadership with my daughter, who is a producer,” Horowitz remembers. “She produced a big performance. They had a Tokyo performance and a San Francisco performance. The star got stopped at Tokyo customs and was deported. The show was stopped. My daughter felt really bad and said it was all her fault, what am I going to do?

And I said, yes, it’s all your fault, but you can only go forward. There is no backwards. When you’re in a leadership position, there’s only forward.”

~

A few months into building Opsware, EDS, which now encompassed 90% of their revenue, began to spot bugs in the new product. Horowitz was worried. If EDS left, Opsware — their last hurrah — would truly be dead.

To understand Horowitz’s next move, one must look to Andy Grove, the founder of Intel and a mentor of Horowitz’s. In 1994, Intel was a $10B+ producer of computer chips, the largest in the world. They had just launched their Pentium processor. Then, a defect in their chips got caught in the crosshairs of an internet forum, where a string of comments pointed out the issue as worrisome. Intel had researched the issue internally and had not found it to be a problem. Still, the rumors began to grow.

Soon, it got into the ears of more mainstream media. Speculation abounded. The impact hit when IBM decided to stop shipment of all Pentium-based computers. Intel had tried reasoning with customers with careful arguments and white papers, but that wasn’t enough to beat the rumors.

So Intel created a war room, conference room 528. In this war room, they set up an organization that could answer the flood of phone calls that was coming in. People from all over the company stepped in to help. Marketing, designers, engineers. Intel decided to replace everyone’s chips and create a service network to handle the physical replacements. And they pulled their way through the crisis.

Horowitz’s first decision was to pull an Andy Grove — he created a war room and made it so that no one on the team could have a question that took more than 24 hours to answer. And he restructured the whole organization. In some ways, it was like creating an entire building, ground floor to the roof, and then deciding to tear it down to make something better.

Nobody called it a pivot in those days. They were just like — oh, they’re going bankrupt and this is how they’re going to stave it off.

“It was wild,” he laughs. “A great solution for people feeling like they don’t have permission to fix things is that they meet with the CEO every day and you remove whatever’s in their way. You tell them — nothing can get in your way. Not resources, approval, someone saying ‘I didn’t know I could do that.’ When you do that, the first meeting is an hour. Within a week, it’s three minutes. People feel that they have the power to make a difference. I use the technique with CEOs all the time. People think it’s somebody who’s in their way when in reality it’s the system.”

“I always say destroy the system when you need to. When leaders get too attached to the system because it got them where they are, the system ends up destroying the work. And people end up blaming each other.”

Eventually, in 2007, Opsware sold to HP for $1.6B. By 2009, Horowitz and Andreessen would go on to start venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

~

March 2023 is not so different from 2001. Founders with all of the right materials — the product, the market, the customer interest — are being affected by external circumstances. The largest bank run in American history, the constant reckonings hitting the crypto industry, the rising interest rates.

There are merits to revisiting Horowitz’s story today. Just like Horowitz learned from Grove, countless founders have learned from his story. Take Alex Rampell, co-founder of fintech startups like TrialPay and Affirm, who tweeted out a long thread about his own pivot in 2012. Trialpay’s revenue had dropped from $77M in 2012 to $55M in 2013 due to Facebook and Apple deciding to own payments. Team members were leaving. Potential buyers were ghosting them. It was a similar moment of desperation to Loudcloud.

Rampell made several decisions, including one that will be familiar to anyone who knows Horowitz’s story: he chose to spin out an offline affiliate network and sold it to Coupons Inc for $30M. Employees made money and their runway was extended. At the end of his thread, Rampell credits Horowitz for his advice. Others, like Yext’s Howard Lerman, who spun out his company’s pay-per-call business echo similar sentiments.

“The worst thing you can do is give up, because there’s probably a move,” says Horowitz. “You just have to find it. I’m definitely from the Jay-Z school. Forward is the only direction. Can’t be afraid to fail in search of perfection. I see CEOs who are far more successful than me who can't do the things that I can do because I went through what I did.”

Never miss another untold story.

Subscribe for stories, giveaways, event invites, & more.

More Like This