Hedge fund-style investing, for everyone

As active investing grows in popularity, Composer co-founder Benjamin Rollert wants to make Symphonies the new index fund.

Written by Meghna Rao

Photography by Belinda Barcenas

Benjamin Rollert, co-founder and CEO of no-code trading strategy platform Composer, is unique, not least because he's got the will to push through the friction of hard-to-use tools to get what he wants. Like in high school, when he paid $20 a trade to buy stocks over the phone (not even a cellphone, a landline). Or, like he did right before starting Composer in 2020, when he turned to Python to code different trading strategies that he wanted to test out.

"My dad got hurt pretty bad by the dotcom crash and I definitely felt some resentment,” he tells me over Zoom, out of what he describes as “rural Canada.” “We lived in a middle class area that was split between people like us and very wealthy people. And I think I’ve wanted to be financially independent ever since.”

Rollert’s friends wanted in on his strategies and he was happy to oblige. Yet, he’d be the first to tell you that no one should know how to code to invest like the best do. “I really don’t like this idea of, just let institutions do this, you’re not smart enough,” he explains. “There’s a certain elitism in finance and I think it’s insulting.”

So he made a Slack channel where he uploaded his Python scripts. Soon, the channel started to take more upkeep than expected. “Whenever things would break, people would message me. And I’d be like I’m working, I have a job, and my friends would be like well, how do we pay you to quit your stupid job?”

That’s where Rollert’s story as a founder begins. In February 2020, he left his job as a data scientist at venn and went all-in on Composer from Nicaragua, where he was living in his wife’s hometown at the time. By November 2021, Rollert had raised a $5.35M seed round from First Round, Golden Ventures, Not Boring Capital, Basecamp, AVG, and Draft Ventures.

“Over time, the compounding differences on higher returns on capital can have a huge impact on generational wealth,” says Rollert. “And that’s what we want to do. We want to bridge divisions and create generational wealth for people.”

~

In the 1880s, people interested in the stock market would bet on its trajectory at bucket shops that received information via telegram, because brokers would only accept large-volume trades — it was an infamous way to get ripped off and was soon banned. In the 1950s, according to a Brookings study, only 4% of the U.S. population owned stocks directly. In 1975, the index fund was invented; by 1993, the ETF was invented. And by 2022, Gallup reported that 58% of Americans owned stock in some way — either directly or through an employer.

The 2020s have also brought other changes with them. In 2021, r/wallstreetbets helped drive up the market value of Gamestop from $2B to $24B+ over just a few days. And between January 2021 and January 2022, r/algotrading grew from 279,000 users to just under 1.4M.

Retail investors — as in, individuals like you and me — are becoming more interested in active investing. There are many theories why. Income equality has driven people away from passive investing (not everyone feels like it's enough to set money in an S&P index fund and hope it does well); there are lots of options for free trades (including Robinhood, which was the first to do so in 2013); and internet communities like r/algotrading and r/wallstreetbets have a growing braintrust of active investing information and advice.

And there are many startups attempting to answer these new needs. Unusual Whales describes itself as “small financial tools for the little guys” and tracks every completed option trade. Delphia has built an algorithm for retail investors that predicts the future of publicly traded companies seven quarters into the future — it claims its algorithm is “Wall Street-caliber.” Numerai, which says it wants to “build the last hedge fund on the planet,” makes predicting the stock market a data science challenge, and crowdsources and funds investment strategies from around the world.

“Over time, the compounding differences on higher returns on capital can have a huge impact on generational wealth, and that’s what we want to do. We want to bridge divisions and create generational wealth for these people.”

Composer’s approach is distinct — it takes the tools that hedge funds already have and makes them accessible to a wide audience, with simple design. To that end, the team spent months building the platform, asking people questions in Slack groups, built a wait list, researched and iterated, and planned for months before writing code. Rollert even told his investors that they would have to wait a long time for Composer to pick up.

“Design is an important piece of this,” says Rollert, whose first two hires were UX researchers (one of whom he had to pay out-of-pocket and then with the government-based small business loans that were being given out at the start of the pandemic.) “What we’re trying to do is make something accessible to an end user, to manipulate a system or domain that they weren’t able to work with before.”

Users can build and use automated trading strategies, known as Symphonies, that can invest across all liquid securities traded on major U.S. exchanges, all at once. Once a strategy is ready to go, Composer uses a broker API from Alpaca, an API for crypto and stocks, to execute trades.

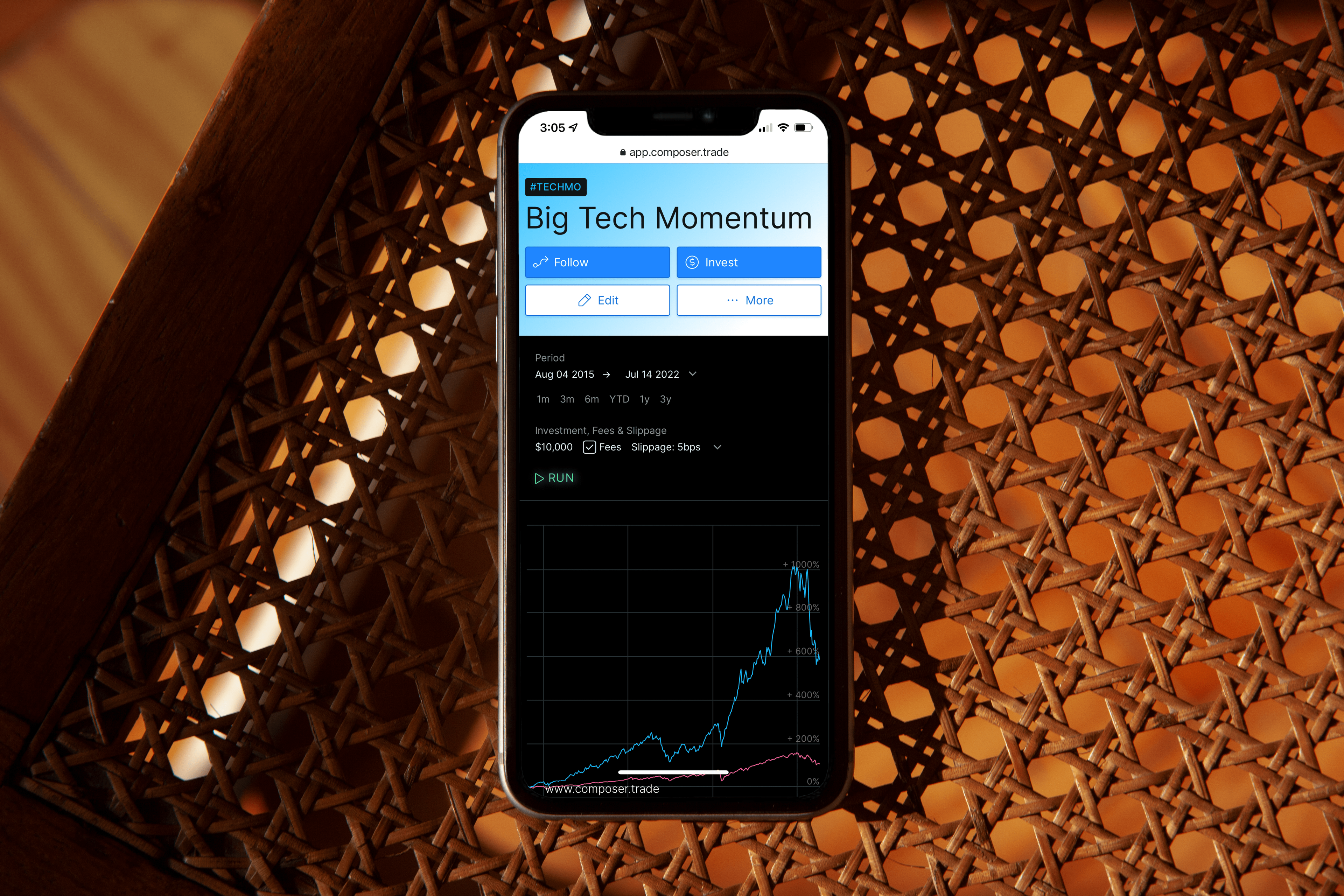

Some Symphonies are put together by Composer, including replications of famously guarded strategies like Ray Dalio’s and new ones like “Big Tech,” which invests once a month in the two best-performing big tech stocks. Others are made by up-and-coming creators, like Packy McCormick or Stoic Capital; users (and superfans) can invest in those whose worldviews they most believe in.

Symphonies can be used as is, edited, merged, or built from the ground up. The site lets users check slippage, or the future outcome on a Symphony if a stock trades lower than expected, add weights to certain stocks in their picks, and match their Symphonies against the performance S&P 500 index (SPY). Big Tech, by the way, has done better than the SPY every single quarter since it started in 2016.

Rollert adds that a key part of Composer’s appeal is backtesting, which produces data on how strategies may have fared in the past. On the platform, a user can check what would have happened if one were to choose Dalio’s famous “weather-any-storm” index in the past — maybe during the pandemic, when it dipped below the SPY for the entire year of 2020. “Every serious portfolio manager backtests their strategies,” Rollert says. “Why can’t retail people do this too?”

~

Rollert cites Jack Bogle’s approach to the market often: go slow and steady. In 1976, Bogle invented the index fund. At the time, it was a complete abstraction, a concept that suggested that one could invest in an index without having to put money into each and every single stock represented. In fact, it was so abstract that it was not popular with retail investors (at least not immediately.)

At first, the index fund existed within the purview of academia; eventually, it escaped and gained the interests of a small group of devout followers. And finally, slowly, it reached a wider market (“like a religion!” exclaims Rollert).

Rollert explains that Composer is similarly starting by catering to a loyal group of users and isn’t planning to go mass market the Robinhood way — at least not at first, because it is “expensive and competitive.” Most of Composer’s initial users, he says, look like himself and those friends who were first interested in investing in his Python-scripted strategies at the start of the pandemic: 401(k)-holders, conservative savers, and professionals who are looking to add some flavor to their existing investments.

“The real secret is that it’s much easier to get product-market fit if you’re representative of the customer you’re building for,” says Rollert. “Then, it’s not like this crazy distraction anymore where you’re trying to imagine what this person wants.”

But Rollert’s vision doesn’t stop there — he says that there’s no reason they can’t approach more novice investors, maybe even the kind that are first getting into investing for the first time. But he takes a measured approach; Rollert is clear that he doesn’t believe that stocks should be the next-gen gambling machine.

“We could definitely go there,” he says. “But maybe they invest with someone they trust. Even if they feel a little intimidated to do it. Maybe this might be their first step to investing better, more wisely. To actually learn the ropes of investing, so it’s not just limited to a wealthy few.”

There are challenges, of course. Even today, only over half of the U.S. (58%) invests in the public directly or indirectly, and this number has dropped since the 2007-08 recession, when it was at 62%. And there are a whole suite of competitors attempting to coerce retail investors from every angle, from companies like Betterment, which has raised $435M in total funding and provides a robo advisor that helps people invest in ETFs, to myriad others closer to Composer on the active investing spectrum with a variety of models, like Webull and Iris.

But Rollert hopes that they’ll soon become enough of a household name that the competition won’t matter. Eventually, Rollert hopes that a Symphony is its own asset, something like the index fund.

“I think of the Symphony as the next layer of abstraction above the index fund,” he says. “And I really hope it is as revolutionary as the index fund.”

More Like This